The Jewel of the Irish Sea

The Isle of Man, also spelled Mann, or in Manx-Gaelic ‘Ellan Vannin’ or ‘Mannin’, is one of the British Isles, located in the Irish Sea off the northwest coast of England. The Island is 52 kilometres long and 22 kilometres wide. In old money that’s 32 miles by 14. It’s home to about 85,000 people. The Island has a 10,000 year history with a strong Celtic and Viking past.

The Isle of Man is not, and never has been, part of the United Kingdom, nor is it part of the European Union. It is not represented at Westminster or in Brussels. The Island is a self-governing British Crown Dependency – as are Jersey and Guernsey in the Channel Islands – with its own parliament (Tynwald) government and laws. Tynwald was established by the Vikings more than 1,000 years ago and is the oldest continuously running parliament in the world. The island has been inhabited since before 6500 BC. Gaelic cultural influence began in the 5th century and the Manx language emerged around that time. In 627, Edwin of Northumbria conquered the Isle of Man along with most of Mercia; followed in the 9th century by the Norsemen.

In 1266, the island became part of Scotland under the Treaty of Perth, which began a period of alternating rule by the kings of Scotland and England. For many centuries the Stanley family (the Earls of Derby) were feudal Kings or Lords of Mann, but in 1736 the last of the Derby line died and the Island passed to the Atholl family, who in what is still seen as an infamous act, ‘sold’ the Island back to the British Crown in 1765 for the sum of £70,000. The Revestment Act, known locally as the ‘Mischief Act’ was, by and large, an attempt to control the ‘running trade’ or smuggling, which was not illegal in the Island and was costing the UK Customs and Excise a great deal. However, the island never became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain or its successor, the United Kingdom: it retained its status as an internally self-governing Crown dependency. His Majesty King Charles is therefore Lord Proprietor of the Island and is formally referred to on the Island as ‘The King, Lord of Mann.’ The Monarch is officially represented on the Island by the Lieutenant Governor.

The most well-known features of the Island are the Manx cat and the Tourist Trophy motorcycle races – the TT – but there is so much more to the Island. Renowned for its rolling hills, natural beauty and quirky attractions, the Isle of Man is known as the jewel of the Irish Sea for good reason; from its unique heritage to its amazing foodie scene, it’s a place not to be missed. So close to the UK, but so different. Oh, and here’s a tip – don’t refer to the UK as ‘the mainland’. You will be told that the Isle of Man is the mainland, which has its own related islands. The UK and Ireland are known as ‘the adjoining islands’ and anywhere that you have to travel over the water to, from the UK to the USA, is known as ‘across’. Here’s just a few of the Island’s features.

Scenery and Landmarks

The Island is beautiful at any time of year. Dramatic landscape and coastlines give way to wooded glens and valleys. In the south of the Island can be found one of Europe’s best preserved Medieval castles, Castle Rushen, the home of the Kings and Lords of Mann. Further west is the now ruined Peel Castle which encompasses the original cathedral, thought to date to the 12th century. The new cathedral, also in Peel, was built in the 1880s. The world’s largest working waterwheel in Laxey, which used to pump water from the mines, is a magnificent site. This feat of Victorian engineering is known as the Lady Isabella and served the mine for 70 years. By contrast, the village of Cregneash gives a taste of what life was like in a 19th-century Manx upland crofting community. Aside from the natural beauty of the Manx countryside and coast, there are plenty of unique landmarks to see.

At 621 metres above sea level, Snaefell is the highest point on the Isle of Man and has breath-taking, panoramic views – at least it does if the weather is good. On a clear day, it is said that from the summit, seven kingdoms can be seen: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man, the Kingdom of Heaven and the kingdom of the sea. The Isle of Man’s rugged and beautiful 100 mile coastline features sandy beaches and impressive cliffs. With a mild climate, rolling hills and an abundance of water sports and other outdoor pursuits, the Island is a popular holiday destination for those who love the great outdoors.

Heritage Railways

The Isle of Man is a ‘must’ for anyone who loves heritage transport. It’s possible to see the majority of the Island by travelling on the impressive network of heritage railways powered by steam, electricity and even horsepower. For example, take a ride along the two mile long Douglas Promenade on a horse tram, and get off at the eastern end to join the Manx Electric Railway to Laxey. From Laxey, the choice is to follow up with a trip on the Snaefell Mountain Railway to the aforementioned summit, or stay with the Electric Railway as it travels on to Ramsey in the north of the Island. The MER was built between 1893 and 1899 and is home to the two oldest working tramcars in the world, along with its original Victorian and Edwardian rolling stock

The Douglas Bay Horse Tramway is the oldest horse-drawn passenger tramway to remain in service anywhere in the world. Established in 1876, the horse trams are an iconic Island attraction. It’s a leisurely way to see the impressive Victorian buildings, in particular the Gaiety Theatre designed by the famous theatre architect, Frank Matcham. From Douglas to the south of the Island runs a Victorian steam railway – the longest narrow-gauge steam line in Britain, recognised as the inspiration for Wilbert Awdry’s Thomas the Tank Engine. Indeed, the Church of England Diocese is still known as Sodor and Man, which Thomas afficionados will recognise. But it’s a proper stream railway, which travels on a fifteen-and-a-half mile long route to the south.

The Coat of Arms, the Flag and the Anthem

The famous Three Legs of Mann appear to have been adopted in the Thirteenth Century as the royal coat of arms for three kings of the Isle of Man whose realm at the time also included the Hebrides in the Western Isles of Scotland (Sodor, of Sodor and Man mentioned above). The emblem was retained when control of the Island passed permanently to the English Crown and one of the earliest remaining depictions of the emblem is on the Manx Sword of State, thought to have been made in 1300 AD. The motto has been associated with the symbol since around the same time: “Quocunque Jeceris Stabit” which literally translates to “Whithersoever you throw it, it will stand.” The ‘three legs’ is often seen as a symbol of Manx independence and resilience. The current Coat of Arms of the Isle of Man were granted by the late Queen by Royal Warrant in July 1996, but undoubtedly formalises a much older local version. The central shield is flanked on the right by a raven and on the left by a peregrine falcon. The raven is a bird of legend and superstition and there are a number of places on the Island which include raven in their names. The Island has a strong Viking element in its history and Odin, the Norse God, was, according to mythology, accompanied by two ravens. During the Tynwald Millennium Year of 1979, a replica of a Viking longship was sailed from Norway to the Isle of Man by a mixed Norwegian and Manx crew. The longship, which is now preserved on the Island, is called ‘Odin’s Raven’. The peregrine is a nod to John Stanley whose eventual successor was created Earl of Derby for his services to Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth. In 1405, Henry IV, King of England, granted the Isle of Man to John Stanley, on condition that Stanley provided to him a pair of peregrine falcons. In addition to this, a pair of peregrines was to be provided to every future English king on his coronation. This formal bestowal of a pair of falcons continued until the coronation of George IV in 1822.

The flag of the Isle of Man shows the three legs, armoured with golden spurs, on a red background. It has been the official flag of the Island since 1st December 1932. As befits a strongly independent people, the Manx have their own National Anthem, which was written in 1907 by William Henry Gill and based on an old folk tune. It boasts eight verses, but it is usual to sing only the first verse, occasionally augmented by the eighth verse. The British anthem: ‘God Save our Gracious King’ is also sung to honour the Lord of Man, but it is called the ‘Royal Anthem’, never the National Anthem.

Language and Culture

Manx Gaelic, which is one of six Celtic languages, the others being Irish, Scots Gaelic, Welsh, Breton and Cornish was the main language of the Island until the late 1800s. Many native Manx speakers couldn’t speak English at all. But it declined, in part due to the fact that English was the language of the upper classes, so parents who wanted their children to ‘better themselves’ insisted that they learnt English. By the 1960s, as few as 200 people could speak the language and the last native Manx speaker died in 1974. However, a massive effort at revival started at the end of the last century and it has had a huge impact. Now there is even a Manx language primary school in which all subjects are taught in the language, with more than 60 bilingual pupils attending. Manx is taught in a less comprehensive way in other schools across the island. Manx can be found everywhere, especially on anything produced by, or part of, the Isle of Man Government. The language is now part of the unique culture of the Island.

Music has always been an important part of Manx life. In a similar action to the resurrection of Manx Gaelic, several leading members of the community in the late 19th century joined forces on a rescue mission to collect Manx folk music from Manx people before it was forgotten. They took down over 300 melodies, mostly without words, from which a collection with new lyrics was published in 1896. A parallel project which prioritised song texts over musical notation appeared in the same year. Sundry others also did sterling work in this area, with the result that there is now a wealth of musical resources which remains popular today. Manx traditional music and dance have a close relationship – dancing popularised traditional tunes during the 1940s and ’50s. By the 1960s and ’70s, newly founded groups brought new life to many of the songs.

Today, Manx groups continue to enjoy international success, with both musicians and dancers being featured in the world’s media, winning many medals. Manx Traditional Dance is still very popular, with the first contemporary troop – Manx Folk Dance Society – being formed in 1951 with regional chapters and a national team. They danced in a national costume which they developed for the purpose. Many groups have grown out of this first society, some using the traditional costume and some not. Manx dancers have been successful in competition on and off the Island, as well as competing in our own the Manx Folk Awards and festivals, especially the annual ‘Manx Competitive Music, Speech and Dance Festival’ known locally as ‘the Guild’. The Guild, which was initially for choirs, began in 1892 and held over just one day. Solo singing was soon included and later the festival was extended to a wide range of music, spoken word and dance. The Guild is now held over nine days and features over 200 classes.

Tynwald

Tynwald is the Parliament of the Isle of Man. It makes laws, decides how public money should be spent, scrutinises the work of the Isle of Man Government and debates important issues. It is a ‘tricameral’ parliament, which means it has three ‘chambers’. The House of Keys and the Legislative Council sit separately and then join together to form Tynwald Court. All three chambers usually sit in the Legislative Buildings in Douglas, the Island’s capital. The building is known locally as the ‘Wedding Cake’ and one look at the picture will clearly show why. Once a year Tynwald Court meets in an open air ceremony held at Tynwald Hill in St John’s. This day is a national holiday for the Island, and the laws passed during the year are proclaimed in both Manx Gaelic and English.

Tynwald Hill is one of the Island’s most distinctive landmarks and is the traditional ancient meeting place of the Manx parliamentary assembly, date back to the Viking settlements which began in the eighth century AD. The name Tynwald is derived from the Old Norse word Þingvǫllr meaning ‘the meeting place of the assembly’. At the Viking Assembly, new laws would have been enacted and disputes settled. No weapons were allowed in the boundaries of the meeting site. Swords, spears, axes and knives would have been left outside the fence that marked the area of the court; to this day the outdoor ceremony commences with the ‘fencing of the Court’. The four-tiered hill itself is an artificial mound, stepped in profile, approximately 25m in diameter at the base, and 3.6m high and is thought to be made with soil from all of the Island’s 17 ancient parishes to symbolise the King’s authority over all of the Island.

Currency and Stamps

The Island issues its own currency: the Manx pound, which is equivalent in value to its United Kingdom counterpart, although it cannot be spent outside of the Isle of Man. However all notes and coins that are legal tender in any part of the United Kingdom (e.g. Bank of England notes) are legal tender within the Isle of Man. Coins are also issued, in the same denominations as the UK ones, but the designs are many and varied and celebrate elements of Manx life. The £1 note is still in circulation, although in practice they are almost never found now.

The TT Races

Every May and June the Isle of Man turns into motorcycle nirvana as it hosts the Tourist Trophy – more commonly known now as ‘the TT’. The world’s greatest road racers gather to test themselves against the incredible ‘Mountain Course’ – a 37.73 mile route on the island’s public roads, although they are, of course, closed for the races. The challenging TT has given the Isle of Man an international reputation as the Road Racing Capital of the World. The races began in 1907 and have continued every year with very few missed years; the most notable being the World Wars and the recent pandemic. The Island is transformed for 2 weeks as fans flock into the Island and motorbikes line the streets. The first TT Races were held in 1907 at St John’s with 27 competitors racing 10 bone-shaking laps of a 15 mile circuit of public roads. In 1911 this short circuit was replaced by the 37½ mile Mountain Course. A few years later the course changed again to follow the route which still forms the 37¾ mile circuit for today’s races. The TT Races, then and now are a test of endurance for both rider and machine and an opportunity for manufacturers to push the reliability and technological innovations of their latest motorcycle designs to the limit.

RNLI and Sir William Hillary

RNLI lifeboat crews protect hundreds of communities around the British Isles through their 24 hour search and rescue service, operated by a fleet of over 400 lifeboats. The crew are primarily volunteers and are prepared to drop everything and risk their lives to save others at a moment’s notice in often difficult and sometimes dangerous situations. Most people on the Isle of Man are aware – and proud of – the fact that the Royal National Lifeboat Institution was first founded here, by Sir William Hillary. Living in Douglas, Hillary saw the treacherous nature of the sea first-hand. In the early 19th century there was an average of 1,800 shipwrecks a year around our coasts, and were just an accepted way of life at sea. But Hilary refused to sit by and watch people drown and, with the help of local people, saved many lives. In 1823, he made an impassioned appeal to the nation, calling for a service dedicated to saving lives at sea. If you take a stroll up to Douglas Head, you can salute his statue, as he stares out towards the Tower of Refuge, which he caused to be built on Conister Rock. He is buried in the churchyard at St George’s Church in Douglas.

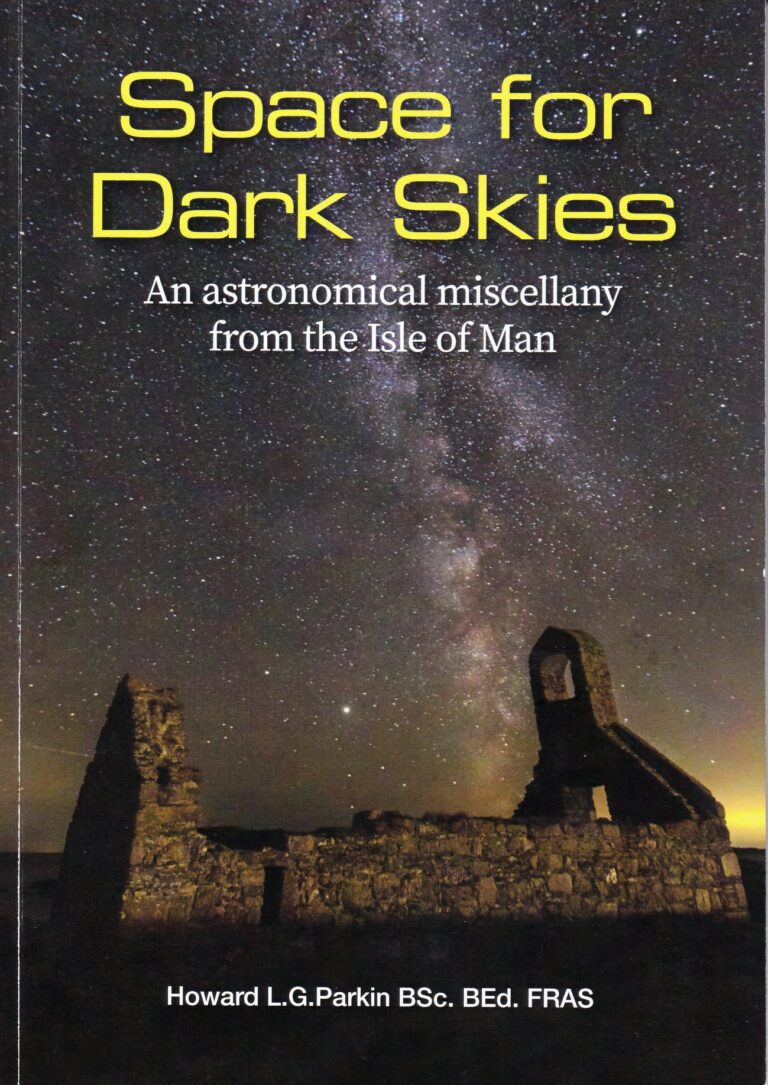

Dark Skies

There are 26 official Dark Sky Discovery Sites dotted around the Island and most are easily accessible. All of them are classed as ‘Milky Way’ sites—this means that not only can the seven main stars in the winter constellation Orion be seen, but also the Milky Way is visible to the naked eye. And for the really lucky stargazer, the Northern Lights are occasionally visible from the Island. The Government has produced a free booklet which can be found at this link and for more in-depth information, Howard Parkin, joint winner of the British Astronomical Society’s 2021 Sir Patrick Moore Prize can’t be bettered. You can contact him here – via the Astromanx Facebook page

Unique Wildlife

The Island is the only entire nation to be a member of the UNESCO world network of Biosphere Reserves. UNESCO defines this as “sites for testing interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and managing changes and interactions between social and ecological systems … They are places that provide local solutions to global challenges [and] include terrestrial, marine and coastal ecosystems”. Surrounded by vast, glistening waters, the Isle of Man is home to a diverse array of marine life, ranging from tiny sea snails and seaweeds to much larger mammals. It is possible to spot dolphins, seals, basking sharks, porpoises or whales, from land or from one of the many boat trips available. Manx Loaghtan sheep, a rare breed of sheep with up to six horns, and the distinctive tailless Manx cat are quite easy to find around the island. Native to the Isle of Man, the two animals are heavily entwined into the Manx environment, history and culture. There are even wallabies living in the wild, after some escaped from the Wildlife Park in the 1960s. However, there are some ‘every day’ creatures that are not found on the Island, such as snakes, voles, badgers, squirrels and foxes.

More information

For more information, here’s some website links:

www.visitisleofman.com

www.ourisland.im

www.gov.im

www.lonelyplanet.com

www.culturevannin.im

And for the TT Races:

www.iomtt.com/tt-info

Page Headers

Pictures on the other pages of this website were all taken by Heather in the Isle of Man and the locations are:

Home: Kallow Point, Port St Mary

Who Am I: Peel Marina

Services: Niarbyl

What’s it all: Monk’s Bridge, Ballasalla

Blog: Laxey Wheel

Small print: Peel Castle

IOM: Douglas Bay

Contact: Douglas Lighthouse

Vouchers: Rue Point